CURSING THE CURSIVE

A LOST ART

Cursive handwriting used to be the standard when writing a letter to someone. However, now in the 21st century, handwriting a letter to someone is the exception, rather than the rule. In 2010, the U.S. government officially removed cursive from the required Common Core Standards for K-12 education. And frankly, with laptops and tablets replacing paper, the need to learn to keyboard has become more important. So it is truly a lost and dying skill.

However, this skill was alive and well in the 1940’s, as is evident by my uncle’s writings. Honestly, one of the things I enjoyed most, and I hope readers did as well, was the step back in time that the letters provided. Handwritten letters hold a certain personal touch, much more than an email or text message – with or without emoji’s. When you combine this with the many abbreviated words he used, such as ‘em for them, tho’ for though, or ‘cause for because, it brought me even closer to hearing the way he spoke – to hearing his voice.

CHALLENGES

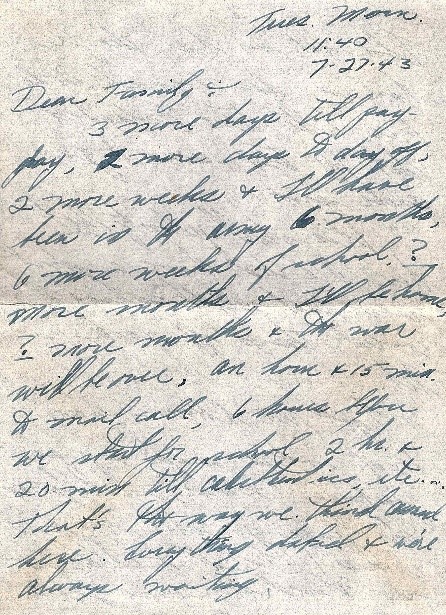

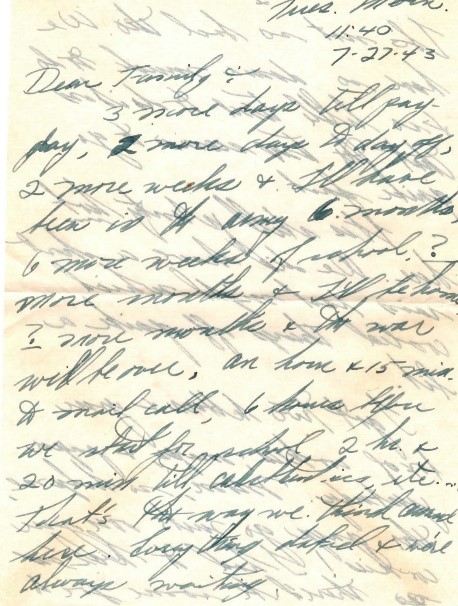

Knowing that his penmanship was difficult to read at times, my uncle made attempts to change the way he wrote, but none of these lasted very long and frankly weren’t much better than his default cursive. Also, I can’t be certain but he does mention several times about being low or out of ink, so I believe he was primarily using a fountain pen and ink well, and at times a pencil.

He also used a variety of different paper types though out his time in the service. Some of the paper survived the almost 80 years of sub-standard storage, while others did not fare so well. In an effort to minimize the weight of the letters, soldiers would sometimes use very thin, onion skin type paper, and my uncle would always write on both sides of the page. This solved the weight problem, but fast forward 80 years and try to scan this paper with a very bright lite and it becomes translucent and a mess of cursive chicken scratches bleeding over each other. So, at the suggestion by my QC team, I was able to resolve the issue by placing a black background on the letter to eliminate the reflective feature of the scanning – this worked – and made the letters much more presentable. As seen by this before and after example below.

As you can see the hurriedly, cursive writing, on sometimes thin paper, that by the time I got my hands on it, was aged and deteriorating, made it very difficult to decipher the message. This was really what led to the decision to transcribe the letters. I started with a few, like the Father’s Day letter he sent to his father (my grandfather, Perry Whitacre) or those that he sent directly to his brother (my father, Dale Whitacre). These cherry-picked letters really started to give me a glimpse inside the type of very close family they were.

TRANSCRIBING

I kept my family informed on the progress I was making with scanning and transcribing the letters. They were anxious and excited to get access to the information held within the letters as well. Transcribing was a lengthy process, about 18 months. Throughout the letters my uncle would refer to things I had never heard of, like “white oleo”, or all sorts of military terms and acronyms. These all had to be researched and referenced.

He also constantly mentions friends and family members – these all had to be researched and referenced. I figured, if I didn’t know what and/or who he was talking about, nobody else probably would either.

A BOOK?

My thoughts of putting the letters into book form were originally limited to only fifteen or twenty copies for the family. But after contacting a publisher, they were quite excited to see a finished manuscript. So, I worked on several different layouts that I thought would present the transcribed letters in a way that would convey all the information the envelope held, as well as the body of the letter itself. I thought it was very important that the letters were transcribed exactly as they were, for authenticity.

EDITS

Initially the only edits I planned to make were punctuation and paragraphing for ease of reading. However, in transcribing I ran into some racial terms that were much more common place than they are in today’s world. This was something I truly battled with. Wanting to keep the authenticity, but understanding that the 1940’s were a different time. While also being personally and adamantly against such demeaning language and the hate it holds. Ultimately my decision was that if my name is associated with it, I will not allow that type of language. So I made edits where I saw necessary.

FINISHED PRODUCT

In the end it came to a total of 335 letters that honestly are more focused on a young man’s love of family (and Ruth Cross) and country, America in the 1940’s, and his path serving in the Army Air Force – Than it is about World War 2. My surprise was that it’s not just information about him as a person, it’s the story of his life.

Be Swell

Marty Whitacre

leave a Comment

The website won’t display your email address. Please feel free to leave your feedback!